Imagine that you have been designing a programming language for over 30 years and that it gradually became widely used across the globe. Some of the decisions you made at the beginning were excellent and contributed to the success of your project. Some others, however, were not the best: over the years you and your users realized that the world would have been a better place if those choices you made eons ago were slightly different.

You keep evolving your language, adding useful features and keeping it up to speed with the competition. The bad choices and older (now obsolete) constructs still linger.

You try removing the most dangerous and least used aspects of the language, and while their dismissal is highly successful, some users will undoubtedly be hindered by it. For more popular constructs, you attempt deprecation: a large part of the community welcomes it and migrates their codebases, while another finds the work required to achieve conformance either unjustifiably large or impossible due to legacy dependencies or licensing issues.

There seems to be no way out until you stumble on this post. Its author makes an incredible claim, worthy of the worst clickbait advertisement:

What if I told you that I could fix all of your problems? Even better, what if I told you that backward-compatibility will never be broken and that migration to newer versions of your language could be automated?

At this point, you immediately think that this guy must be insane. Then he says…

Also, someone already did it. And it works.

Now you’re interested.

rust editions

In the C++ community, Rust is a controversial topic. Some people seem frightened by it, and most are justifiably skeptical. Maybe we should start saying “R-word” like we say “M-word” instead of monad.

Anyway, I believe that Rust elegantly solved the problem of language evolution, by using a system called “Editions”.

From “What are Editions?”

Every two or three years, we’ll be producing a new edition of Rust. Each edition brings together the features that have landed into a clear package, with fully updated documentation and tooling.

When a new edition becomes available in the compiler, crates must explicitly opt in to it to take full advantage. This opt in enables editions to contain incompatible changes, like adding a new keyword that might conflict with identifiers in code, or turning warnings into errors.

A Rust compiler will support all editions that existed prior to the compiler’s release, and can link crates of any supported editions together.

Edition changes only affect the way the compiler initially parses the code.

Therefore, if you’re using Rust 2015, and one of your dependencies uses Rust 2018, it all works just fine. The opposite situation works as well.

Editions guarantee the following:

Language designers can make “breaking” changes, like removing features or adding keywords;

Users can opt-in to new editions, and their code is backward-compatible with the existing one.

Additionally, automatic migration from an older edition to a new one is often possible.

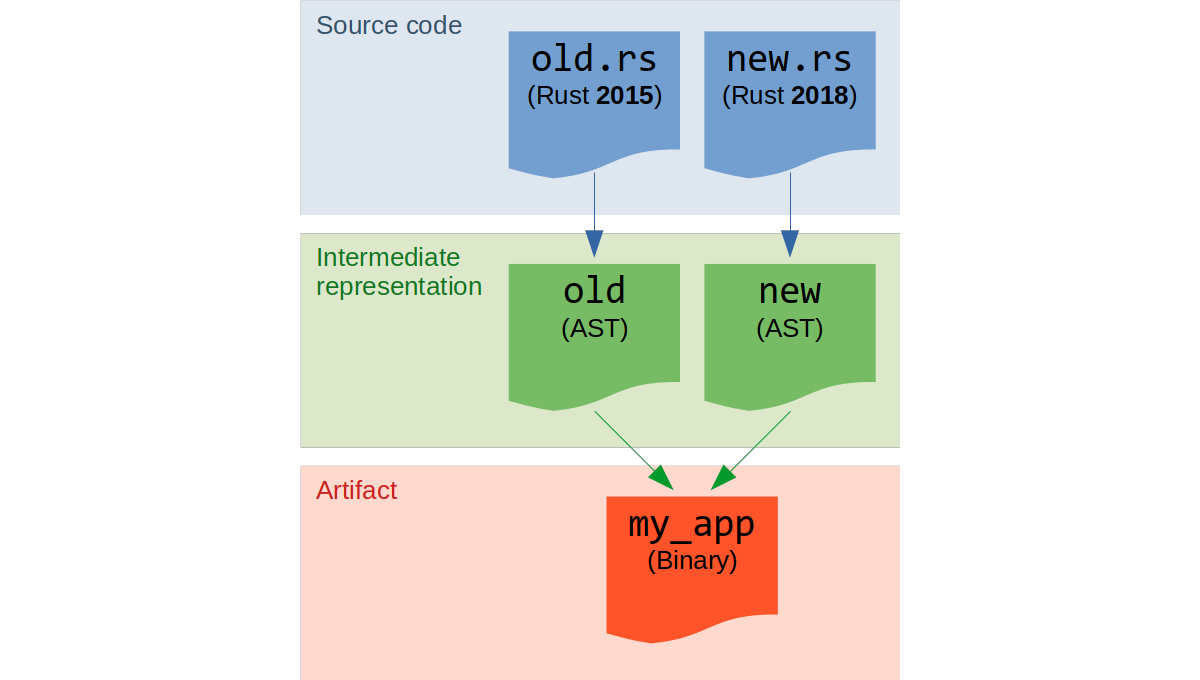

Everything I described above is possible because Rust is module-based, and doesn’t support textual inclusion like C++’s #include preprocessor statement. In visual form, this is roughly what happens:

A nice example of a “breaking” change introduced in Rust 2018 is the requirement of using the dyn keyword for run-time polymorphism, making the presence of type erasure obvious to readers:

// Rust 2015

fn foo() -> Box<Trait> { /* ... */ }

// Rust 2018

fn foo() -> Box<dyn Trait> { /* ... */ }

// ^~~

// RequiredFinally, Rust provides tooling to automatically migrate old code to newer editions. While not perfect, it makes the migration experience as painless as possible.

c++ epochs

The goal of this blog post is to convince you that we need an equivalent of Rust Editions in C++, and that it is possible and a good idea. In this article, I am going to refer to this hypothetical mechanism as “C++ Epochs”, inspired by the previous name given to Editions.

Our key to success is the introduction of Modules, which is now part of the C++20 Standard.

Since Modules are self-contained units that are isolated from preprocessor macros and textual inclusion, we could have a module-level epoch switch.

This would allow users to select what epoch to use. To avoid creating a plethora of dialects, I propose that each Standard should introduce a new epoch. Instead of having many little knobs, people would have to opt-in to every new Standard.

what we could change

We could finally improve the safety and expressiveness of the language, and fix many constructs that cause frustration and bugs. For example:

Replace

std::initializer_listwith a better alternative that allows moves, without changing the usage syntax;Achieve a truly uniform initialization syntax, maybe removing C-style initialization and rectifying quirks in today’s braced-initialization;

Remove older features that have a superior counterpart, like

typedef;Safely introduce new keywords (e.g.

await);Reduce the number of contexts in which implicit conversions can happen, reducing the likelihood of bugs;

Enforce Core Guidelines in the language itself (e.g. “a member function shall be one of

virtual/override/final”);Disallow uninitialized variables from being instantiated, unless a more explicit syntax is used (e.g.

int x = void;);Introduce a placeholder name (e.g.

_) without risking name collisions.

More drastic changes could also be considered:

Make most entities

constby default, and allow using themutablekeyword to enable mutability;Make types and functions

[[nodiscard]]by default, and introduce a new[[discardable]]attribute;Enforce one declaration style (e.g. AAA or trailing return types);

Make

explicitthe default, and introduce animplicitkeyword;Get rid of dangerous constructs that only exist to maintain C compatibility, or introduce

unsafeblocks where they are required to live.

why are we not doing it?

There are three main reasons why we are not pursuing this path:

Modules are brand new, and we still need to gain experience;

Nobody has formally proposed something like “C++ Epochs”;

Many veterans in the committee are opposed to the idea.

The first two points are non-issues - time will resolve them. Let me elaborate on (3) a little big: I informally floated the idea of epochs around in the WG21 Jacksonville 2018 meeting and was met with heavy resistance. I will list the concerns I have received and reply to them.

Introducing module-level syntax switches would lead to the creation of many dialects.

This is a complete misunderstanding of what I am proposing here. First of all, there would be a single switch, not many coexisting knobs. The switch would allow people to choose between language epochs that are linearly ordered chronologically - no forks or branches. The Standard committee would still be in charge of deciding when to create a new epoch and in charge of its contents. “Breaking” changes would not be made lightly.

There absolutely is zero risk of creating many different dialects here.

Module-level switches would lead to community fragmentation.

Similarly to the point above, this is again a misunderstanding of the proposal. The “fragmentation” would not be any worse than what we have today (i.e. some people can use C++14, some can use C++17, some are not allowed to use exceptions and some others are). Adding epochs would not change that situation. If every Standard introduces a single new epoch, then people will have to opt-in to the new Standard or not, which is exactly what happens today.

Finally, epochs are not going to radically change what C++ is. An epoch might introduce small syntactical changes and safer defaults, but it would not be a different language by any means.

Module-level switches would make the language more complicated.

False. In fact, it’s exactly the opposite! Language rules could be greatly simplified in newer epochs, and many obsolete/dangerous constructs could be completely removed. The Standard would get bigger, and possibly divided by epochs. However, the committee could focus on the latest epoch, while only supporting previous ones with bug fixes.

Over time, WG21’s work would become easier as the language becomes slimmer and saner.

Module-level switches would make the lives of compiler developers even harder.

There is some truth here. However, in one way or another, all remarkable features make the lives of compiler developers harder. If anything, thanks to Rust’s experience, we have proof that module-level switches can be implemented and that they work.

Introducing module-level switches would create a schism similar to Python 2 and Python 3.

Again, a misunderstanding. Python 2 code is not compatible with Python 3 code. Code written in a previous C++ epoch would be compatible with code written in a newer one.

Lastly, I want to make this claim: if the Standard committee doesn’t do this, someone else will. It might start as a hobby project of some compiler enthusiast experimenting with modules. They will figure out: “hey, I can change C++’s syntax to something I prefer here by adding a module-level switch”. Then it will grow, and more people will use it, and… that’s how the community will be split.

what next?

We have an opportunity to fix, simplify, and evolve C++, and I believe we should take it.

I am happy to spend time to write a proposal, provided that the feedback to this idea is mostly positive. I would also like to hear the thoughts of Modules experts, compiler developers, and WG21 veterans before I start working on a paper.

Feel free to comment below, on Reddit, or to contact me directly.

additional resources

Here are some interesting discussions on the subject:

Here’s my previous article where I discuss my Jacksonville meeting experience, including the informal epochs proposal: