The past few days have been “interesting”. My Twitter has been raided by the part of the gamedev community that doesn’t see much value in Modern C++ and prefers writing code with a very low level of abstraction. However, this time I didn’t start it, unlike a while ago…

This article (1) tells the story of the heated discussions one of my tweets spawned, (2) analyzes some common requirements and misconceptions game developers have, and (3) provides a list of Modern C++ features which every game developer should use.

Enjoy.

background

I am working on a virtual reality mod for Quake. Actually, calling it a “mod” is a bit diminishing: not only I have spent a considerable amount of time working on my fork of the QuakeSpasm engine to add VR support, but I’ve also changed pretty much every game mechanic to turn the classic into a first-class virtual reality experience:

The Quake VR project has been a great source of fun and a fantastic learning experience for me. I am getting in a very intimate relationship with Quake’s codebase (including all its quirks and weirdnesses), getting accustomed to OpenVR, and dabbling in OpenGL graphics programming that I had never done before (e.g. geometry shaders).

I am also using this project as an opportunity to experiment with C++17 features, and to generally enjoy myself with Modern C++. One of my favorite additions to the 2017 standard of the language is “fold expressions”. A fold expression basically reduces a parameter pack into a single result, but can also be used to arbitrarily generate code for every element in the pack.

In order to add textured particles and remove the overhead of immediate mode OpenGL, I rewrote Quake’s particle system from scratch. Doing that, I found myself needing to stitch together some images to create a texture atlas, in order to avoid unnecessarily binding and unbinding textures. In my particular scenario, all the texture file paths are hardcoded, as I have no interest or need to implement custom particle textures. Therefore, I decided to experiment with fold expressions:

The more I use #cpp packs and fold expressions, the more I wish they were available at run-time. They are a very elegant and convenient way of expressing some operations. (@seanbax had the right idea!)

— Vittorio Romeo (@supahvee1234) May 11, 2020

As an example, here's primitive generation of a texture atlas for Quake VR. pic.twitter.com/X7tKrvPq0j

As you can see from my tweet, I am using a parameter pack to pass all

the images to stitch together to the stitchImages variadic

template function. This is obviously not necessary, as a run-time

container would also work, but - surprisingly - it leads to some really

elegant code1:

template <typename... Images>

TextureAtlas stitchImages(const Images&... images)

{

const auto width = (images.width + ...);

const auto height = std::max({images.height...});

// ...Focus on the definition of width and

height: using a fold expression allows to very concisely

and unambiguously express the intention of (1) summing all the images’

widths together and (2) finding the maximum height between all the

images. Furthermore, this approach allows both variables to be

const-qualified, avoiding accidental mutation and

decreasing cognitive overhead for readers. Cognitive overhead is reduced

thanks to the fact that those two variables are guaranteed to not change

their value throughout their lifetime, thus allowing a reader to focus

their attention on the “moving parts” of the function body.

Compare the above definitions to a loop-based run-time version:

TextureAtlas stitchImages(const std::vector<Image>& images)

{

std::size_t width = 0;

for(const auto& img : images)

{

width += img.width;

}

std::size_t maxHeight = 0;

for(const auto& img : images)

{

maxHeight = std::max(maxHeight, img.height);

}

// ...I believe the above solution is, honestly speaking, terrible. First

of all, we are using std::size_t, which is not guaranteed

to match the type of Image::width. To be (pedantically)

correct,

decltype(std::declval<const Image&>().width)

should be used, which is verbose. Regardless, the code is still

unnecessarily verbose - the amount of syntactic noise makes me wonder if

the code is correct when I look at it, as there are more places where a

defect could have been introduced. Finally, we lose

const-correctness, including its safety and readability

benefits.

Obviously, <algorithm> comes to the rescue!

…right? Well, you be the judge:

TextureAtlas stitchImages(const std::vector<Image>& images)

{

const auto width = std::accumulate(images.begin(), images.end(), 0

[](const std::size_t acc, const Image& img)

{

return acc + img.width;

});

const auto height = std::max_element(images.begin(), images.end(),

[](const Image& imgA, const Image& imgB)

{

return imgA.height < imgB.height;

})->height;

// ...It sucks. We get const-correctness and avoid accidental

type mismatches for height, but there is an unbelievable

amount of noise and boilerplate for a very simple task. In contrast,

think about how you would perform this task in other languages such as

Python:

def stitchImages(images):

width = sum(img.width for img in images)

height = max(img.height for img in images)

# ...Concise, simple, and self-explanatory. Fold expressions are remarkably similar, if not better:

template <typename... Images>

TextureAtlas stitchImages(const Images&... images)

{

const auto width = (images.width + ...);

const auto height = std::max({images.height...});

// ...I really like the above code snippet, and I would strongly encourage people to write code like that in production… if it wasn’t for the fact that fold expressions are purely a compile-time feature. Which brings up the entire point of my tweet:

The more I use #cpp packs and fold expressions, the more I wish they were available at run-time. They are a very elegant and convenient way of expressing some operations. (@seanbax had the right idea!)

The discussion I was trying to spark was on whether or not C++ could get a syntax similar to fold expressions that also worked at run-time, because I believe it is a valuable addition to the language to improve readability, conciseness, and safety all at once.

I tagged Sean Baxter in the original tweet, who created an amazing language called Circle. In a nutshell, it’s an extension of C++ adding a new powerful metaprogramming paradigm and many new features to improve productivity. Definitely worth a look into.

Circle supports “list

comprehensions, slices, ranges, for-expressions, functional folds and

expansion expressions”, even at run-time. In fact, you are able

to write stitchImages in Circle (using run-time data) in a

way that’s very close to the variadic template version:

TextureAtlas stitchImages(const std::vector<Image>& images)

{

const auto width = (images[:].width + ...);

const auto height = std::max({images[:].height...});

// ...[:] is basically compiler magic that allows you to treat

the elements of the vector as if they were a parameter pack. It’s all

syntactic sugar for regular run-time operations that you would perform

using a loop. I find it extremely valuable and I think that is the right

direction forward for C++ - would love to see a paper proposed for

standardization.

outrage

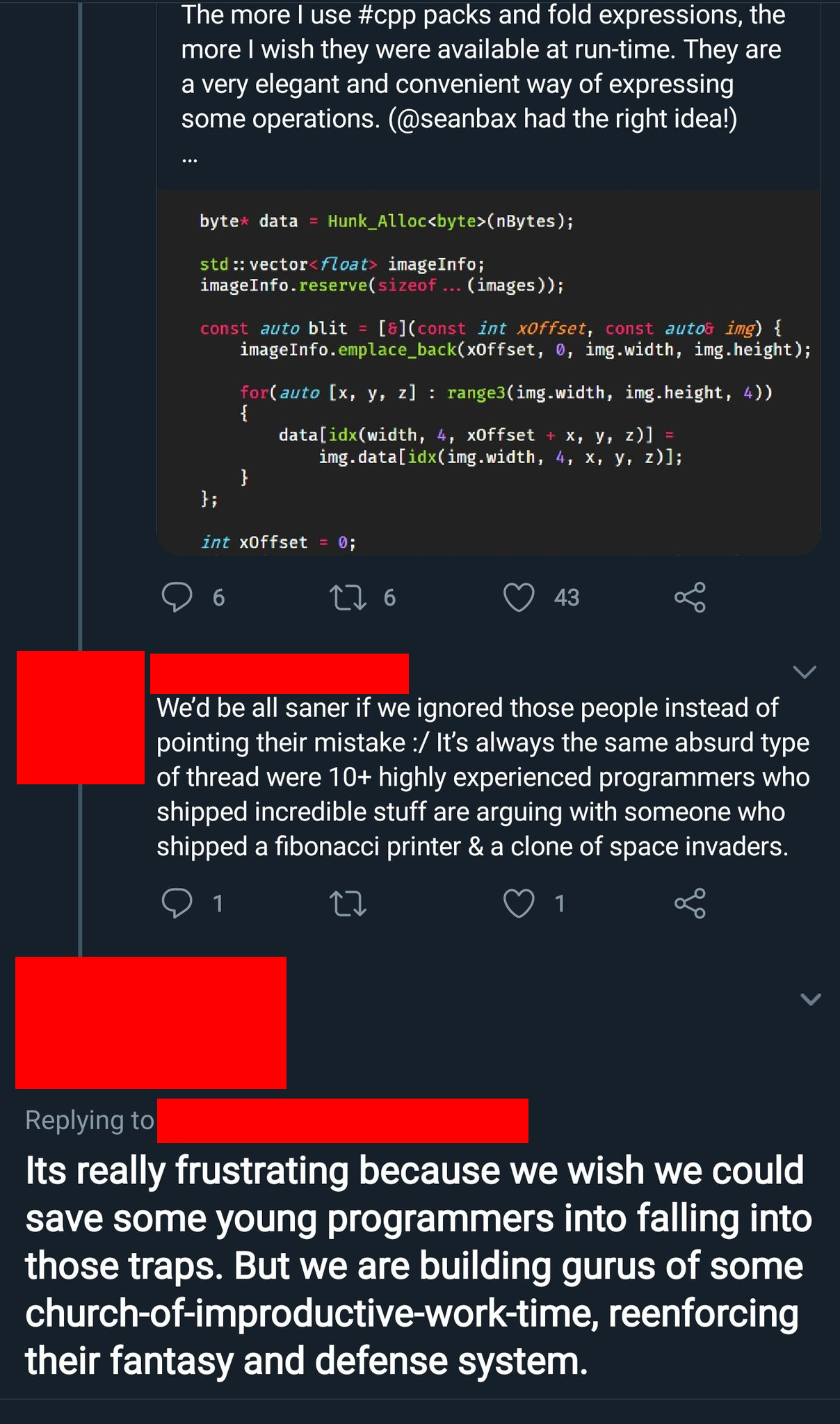

Of course, an observation I made regarding the gap between compile-time and run-time features in C++ in the context of a personal hobby gamedev project attracted the attention of part of the Twitter gamedev community, whose first reaction was naturally to either (1) mockingly retweet my original code snippet, showing one’s followers how “stupid those C++ programmers are”, or (2) comment on how the code was “retarded” and how my tweet was setting a negative example for young developers and should be shunned.

While that’s already sad, I even more disappointed by seeing that some people whose work I truly admire also had something very disheartening to tell me:

Thankfully, I have faced enough hardships in my life so that this kind of bullshit doesn’t phase me (much) anymore. However, imagine a young developer getting this kind of response from one of their idols, to one of their experiments they were eager to share: that would be soul-crushing.

Even if the author of that tweet was generalizing, those kinds of generalization are hurting our community and industry. Somebody experimenting on their personal project and sharing some thoughts to a specific subset of the C++ community isn’t hurting anyone.

I could show many absurd and tasteless tweets I was sent, but that’s not the point of this post. I want to discuss misconceptions regarding Modern C++ in the game development industry.

requirements and misconceptions

Hidden throughout the barrage of snarky remarks or self-righteous observations on how Modern C++ is cancer for the programming industry, there were some really good points raised as well. Many game developers have very specific requirements that the C++ standardization committee is not prioritizing for.

debuggability

The most common requirement, debuggability, is of tremendous importance. There are two ways in which the use of Modern C++ hinders the ability to debug code. It all stems from how Modern C++ encourages the use of “zero-cost abstractions”:

Such abstractions are only zero-cost (at run-time) when compiler optimizations are enabled. When running an application in debug mode, the performance can be hundreds of times worse compared to release mode, which can make a game literally unplayable.

The way such abstractions are often implemented is by leveraging layered architecture and code reuse. These are valuable software engineering principles that allow large projects to scale and grow, but they also tend to cause deep call stacks due to multiple levels of indirection: such depth can make it hard to understand what is going on during debugging. This problem is particularly evident when using standard library facilities, which are notoriously known for having very complicated and deeply-nested implementation details.

These points are fair. The solution that most game developers reach

towards in order to mitigate these points is to simply avoid

abstractions as much as possible, including making extreme decisions

such as not using the standard library at all, or using

std::vector<T>::data() + N instead of

std::vector<T>::operator[](N) (or even not using

containers at all).

However, there is an aspect of those solutions that it is often overlooked. Let’s (reasonably) assume that, apart from situations where you just want to explore a codebase interactively, the frequency of having to debug is linearly proportional to the number of bugs in your program. Let’s also (again, reasonably) assume that the use of battle-tested abstractions designed to improve safety reduces the chance of bugs in your program.

Do you see the conundrum? Of course you’re going to have to debug more if you write error-prone C-like code and avoid utilities that have been refined over decades to help you avoid mistakes.

I am sure there is a balance - not every line of your code should be buried under 20 layers of abstractions, however proper use of the standard library (or custom-made types and functions) would reduce the times debugging is required, as mistakes would be prevented during compilation. Dan Saks gave an excellent talk at CppCon 2016 (which I had the pleasure to attend in person) which touches on this topic a bit - highly recommended:

I think that both sides should converge on this matter:

Standard library implementors and C++ committee members should take this requirement seriously, and brainstorm on how the situation could be improved;

Game developers (and people generally skeptical of Modern C++) should give a chance to a more balanced coding style where carefully chosen abstractions are used to avoid bugs at compile-time whenever possible.

I can also see another interesting opportunity in the space of debugging tools development to mitigate factors that can make one’s debugging experience suboptimal. As an example, a user-friendly way to mark some layers of the call stack as “unimportant” (and remember that information between debugging sessions) could be a good starting point.

However, I am sure of one thing: completely abandoning the safety, readability, flexibility, and expressivity provided by Modern C++ features and abstractions is an extreme and unwise reaction to this problem.

compilation times

Another issue that was brought up multiple times was one that has been covered many and many times before: compilation times. C++ has a notoriously bad reputation for slow compilation times which, in my opinion, was very justified when we didn’t have modern language features. Prior to C++11, any metaprogramming required heavy use of templates, including recursive template instantiations to - for example - simulate type lists. Furthermore, libraries that achieved incredible feats given the limitations of C++03 (such as Boost) while keeping portability with thousands of compiler/platform combinations had to resort to arcane techniques that ultimately led to very slow compilation times.

It is not surprising that, game developers who had poor experiences back in the day, still shudder from the idea of introducing any template or abstraction in their codebase, failing to realize that things are much better nowadays.

One of the biggest misconceptions I’ve been exposed to countless times is that “Modern C++” equals “Standard Library”. That is completely false. Standard library implementations are not optimized for compilation time or debuggability - they need to be (1) general-purpose, (2) easy to maintain and extend, (3) efficient at run-time, (4) compliant to the standard and all its nuances.

This thread on r/cpp

(“unique_ptr - seven calls to dereference - why is this

needed?”) is very telling. The author calls themselves a

“modern C++ skeptic”, and feels (rightfully) justified in their

skepticism by the fact that a simple std::unique_ptr

dereference requires 7 layers of indirection in the call stack.

A more compelling resource is the “Lightweight but still STL-compatible unique pointer” article by the author of the excellent Magnum graphics engine.

The article observes that including the <memory>

header in a project drastically increases compilation times. The author

also tested the implementation of modules at the time, and it didn’t

help much. The author, instead of becoming a crusader against Modern

C++, realizes that the problem lies in the implementation of

std::unique_ptr, and that the latest standards of the

language provide the necessary features for the creation of a

lightweight alternative to std::unique_ptr (which is good

enough for Magnum’s requirements). This thought process leads to the

creation of CorradePointer.h,

a single-header implementation of unique heap-allocated object ownership

that has minimal impact on compilation times.

The point I’m trying to make here is that most of the language features offered by Modern C++ can be used without depending on the standard library. I’m also admitting that the standard library is far from perfect, but that’s understandable as it is a general-purpose tool that needs to satisfy an incredible amount of use cases.

What I just discussed is the misconception that bothers me the most.

If <memory> is too expensive for your compilation

times, why would you ever abandon the safety, convenience, and

readability improvements of std::unique_ptr when you can

implement something similar in about 20 lines of code?

This point can be applied to pretty much every standard library

component (except very low-level ones like

<type_traits>, which do not impact compilation times

significantly).

When you rashly abandon Modern C++ as a whole and become a Twitter keyboard warrior, there are real and important benefits you are missing out that C++ provides.

features matter

In the context of game development, I would not be able to live without many features introduced in C++11/14/17. Some of them are simple quality-of-life improvements that have zero impact on compilation time or debuggability and yet provide an immense amount of value.

I made a list of features which I think (1) are simple, (2) have minimal impact on debuggability and compilation times, and (3) are still extremely valuable.

Let’s get started…

c++11

enum class- great to represent a closet of options or choices. Great for AI, menus, network protocols, “strong typedefs”, and more.Range-based

forloops.auto.Lambda expressions - useful to compartmentalize your code by introducing local functions that bundle related logic together, or to express asynchronous operations more cleanly.

override- sometimesvirtualpolymorphism is useful for games, andoverridehelps avoid mistakes and increase readability. Of course, I am not suggesting you should have anEntityclass with avirtualupdate member function (even though that’s entirely reasonable for smaller games), but any sort of auxiliary system (e.g. scene manager) can benefit from polymorphism.nullptr.Type aliases and template aliases - excellent way to avoid code repetition and make your code more maintainable/flexible, as you can change your types in a single place instead of find-replacing all over your codebase.

Raw string literals - I could not live without these. If I want to embed GLSL code in my game and keep it readable, these are a must. Incredibly useful.

c++14

Binary literals - say goodbye to bitmasks which require mental gymnastics. Just show what your mask is supposed to look like in binary, making it extremely clear which bits are going to be affected.

Digit separators - games are full of hardcoded constants. “Max particles”. “Max entities”. And so on. Make them more readable with a simple

'character - it will be extremely easy to distinguish a100'000from1'000'000.

c++17

Nested namespace definitions - organize your code in a fine-grained manner, avoiding all the annoyance of extra indentation levels.

[[fallthrough]]- best thing since sliced bread, especially because I know you game developers loveswitchstatements. This attribute allows you to be explicit about your intention to fall through, avoiding bugs and increasing readability.[[nodiscard]]- I lied. This is the best thing since sliced bread, especially because I know you game developers hate to use exceptions. Any function returning a value that shouldn’t be ignored (e.g. an error code) can now be decorated with this attribute, causing the compiler to complain if you forget to check an important return value. I use this feature all the time, both at work and in my personal projects. It is a lifesaver.Structured bindings - I also know you like plain and flat

structtypes. I do too. They’re fast, simple, and easy to work with. C++17 makes them even better as you can now destructure their members and give them individual names.

conclusion

I believe that both sides can learn a lot from each other, and that the negativity and toxicity I’ve experienced for a tweet (that was just a personal observation regarding a Modern C++ feature) shows how sad the situation is.

I also strongly believe that every game developer who is skeptical of Modern C++ should stop erroneously thinking of the “Standard Library” as “Modern C++” and should give a try to all the features I listed above. I promise that they will not impact your compilation times, and they will very likely have a positive impact on the quality, readability, and safety of your code.

Finally, my hope is that this post will bring both sides closer together rather than create a new shitstorm - that is not my intention. I enjoy some rivalry, and I do enjoy some arguing… but sometimes it is too much, and the “fun” we have by shouting our opinions at each other should always at least give both sides something to think about, to make each party grow either on a technical or human level.

Peace.

“Elegance” is an objective measurement of the beauty of piece of code. Elegant code is code that scores high according to the official standards of code beauty (OSOCB). You can verify whether your code is elegant or not by running it through

clang-tidy -checks='beauty-standards-code-elegance'.↩︎